Ancient Smells Reveal Secrets Of Egyptian Tomb

Ancient Smells Reveal Secrets Of Egyptian Tomb

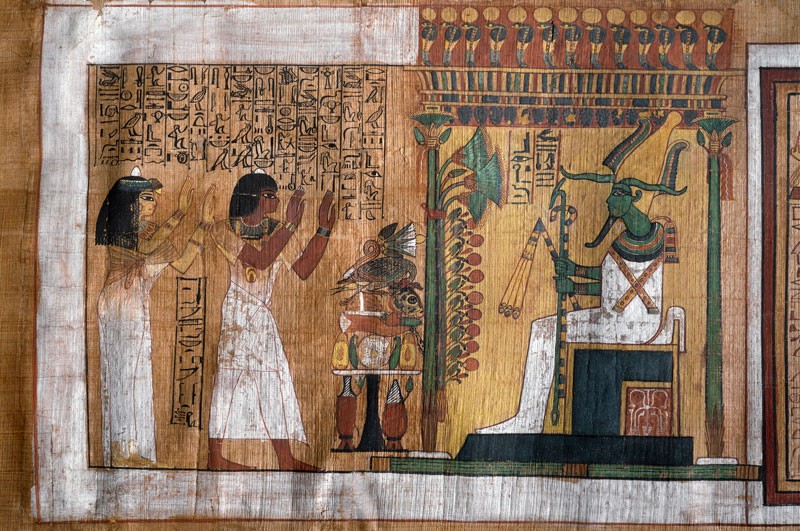

To keep the tomb’s inmates alive in the afterlife, jars were filled with fish, fruit, and beeswax balm.

The jars of food intended to nurture the everlasting souls of two ancient Egyptians are still smelling lovely more than 3,400 years later. These odors were analyzed by a team of archaeologists and analytical chemists to help identify the contents of the jars1. The research demonstrates how the archaeology of smell may help us better comprehend the past and make museum visits more immersive.

The discovery of Kha and Merit’s entire tomb in the Deir el-Medina necropolis in Luxor in 1906 was a watershed moment in Egyptology. The tomb of Kha, a ‘chief of works’ or architect, and Merit, his wife, is the most comprehensive non-royal ancient Egyptian burial yet discovered, offering crucial details about how high-ranking individuals were treated after death.

Ilaria Degano, an analytical chemist at the University of Pisa in Italy, describes the collection as “extraordinary.” “There are also instances of Kha’s ancient Egyptian linen underwear, inscribed with his name, among the artifacts.”

Even after the corpses were brought to the Egyptian Museum in Turin, Italy, the archaeologist who discovered the tomb avoided the desire to unwrap the mummies or peep inside the sealed amphorae, jars, and jugs there, which was unusual for the period. According to Degano, the contents of many of these vessels are still a mystery, albeit there are some clues. “We knew there were some fruity fragrances in the exhibit cases after conversing with the curators,” she explains.

Analyze the odor

Degano and her colleagues put jars and open cups filled with the decaying leftovers of ancient food within plastic bags for several days to gather some of the volatile molecules they still released. The scientists next utilized a mass spectrometer to determine the scent components in each sample. They discovered aldehydes and long-chain hydrocarbons found in beeswax; trimethylamine, which is present in dried fish; and additional aldehydes found in fruits. Degano claims that “two-thirds of the objects yielded some effects.” “It came as a pleasant surprise.”

The results will be used as part of more extensive research to re-examine the tomb’s contents and create a complete picture of non-royal burial rituals around the time Kha and Merit died, some 70 years before Tutankhamun came power.

Scent chemicals have been used to disclose significant facts about ancient Egypt before. Researchers isolated volatile chemicals from linen bandages used to wrap bodies in some of the earliest known Egyptian cemeteries between 6,300 and 5,000 years ago in 2014. The chemicals verified the existence of antibacterial embalming compounds, indicating that Egyptians experimented with mummification 1,500 years earlier than previously assumed.

According to Stephen Buckley, an archaeologist and analytical chemist at the University of York in the United Kingdom, engaged in the 2014 study, odor analysis is still an underexplored area of archaeology. “Archaeologists have overlooked volatiles because they assumed they would have vanished from objects,” he explains. “However, if you truly want to understand the ancient Egyptians, you must enter their realm of fragrance.”

The ancient Egyptians, for example, needed sweet-smelling incense made from fragrant resins. “Temple rites and some burial rituals need incense,” explains Kathryn Bard, an Boston University in Massachusetts archaeologist. Because resin-producing trees did not grow in Egypt, long-distance excursions were required to collect supplies.

Exhibits with more information

Aside from providing further information about former civilizations, old odors could enhance the museum visiting experience. “Smell is a largely unexplored gateway to the communal history,” says University College London’s Cecilia Bembibre. “It can allow us to have a more emotional, personal encounter with the past.”

But, as Bembibre points out, recreating ancient odors is difficult. Because degradation and decomposition can be unpleasant, the smells of an artifact now may differ from the original “smellscape” of a tomb, as described by Bembibre.

Buckley claims that it should be easy to distinguish between the original and decomposition odors with the correct information and expertise. It’s also debatable whether visitors would want to experience an ancient tomb’s complete, potentially unpleasant smellscape. “Curators may want to give folks an option about how far they want to push the olfactory experience,” Buckley suggests.